Birth

The Primal Wound

"There is a big empty hole inside me, and I need to plug it back up. That would be my birth mother.1"

An infant enters the world seeking one thing: their mother. She is food, warmth, comfort, familiarity. Her presence alone can calm her crying baby, regulate the heart rate, breathing, and temperature, and even lower blood pressure. When a newborn is separated from their first mother and handed to their adoptive parents, strangers—however kind or well-intentioned, their brain floods with stress hormones. That early rupture is what we now understand as relinquishment trauma. Research suggests it can echo throughout the lifespan, increasing vulnerability to chronic pain, inflammation, anxiety, attachment difficulties, substance use, mood disorders, generational trauma, fears of abandonment, and more.

People don’t often think of birth as traumatic, but it kind of is. One moment you’re snuggled down in the only world you’ve ever known, and the next, you’re pulled into cold air and blinding lights, surrounded by so much unfamiliarity. Even the smoothest birth experience is a massive transition. For those of us separated from our mothers at birth, that first fracture leaves a mark. We may not recall it with words, but our bodies remember.

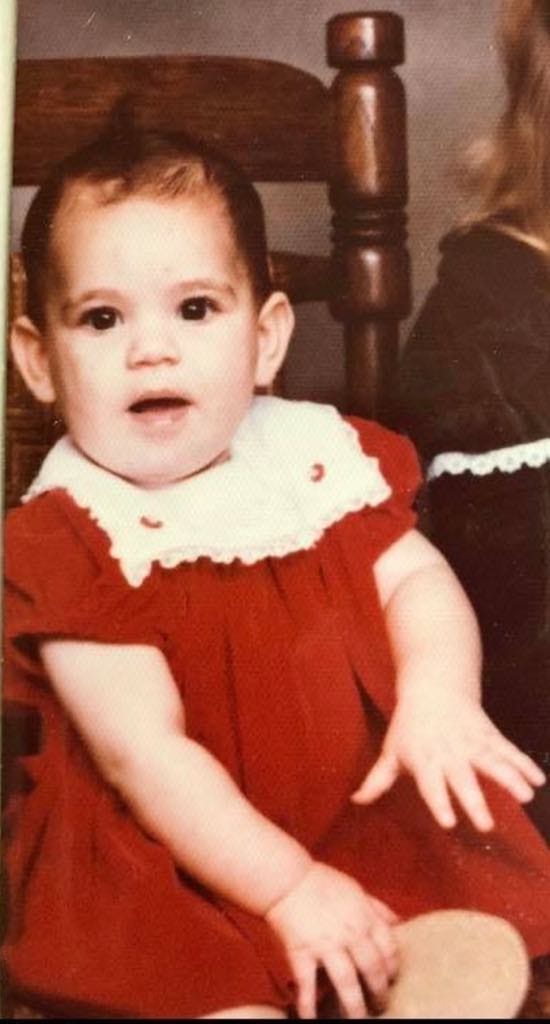

I was four days old when I was adopted. In the time between birth and placement, I stayed in a hospital nursery where holding was discouraged. My maternal aunts have told me how they snuck into the hospital to see me through the nursery window, desperate to take me home. My first mom described sitting at her mother’s dining table, helping prepare Sunday dinner when labor began. She left the hospital, and under her father’s orders, no one spoke of me again.

I imagine the fear my adoptive parents must have felt when they realized how sick I really was. How much easier it could have been if they’d known my first mom had life-threatening asthma, or that she was sick with pneumonia and on steroids for much of her pregnancy. But they didn’t know — because it was a closed adoption. No records. No names. No family medical history. Not even de-identified information that could have drastically improved my quality of life.

At medical appointments throughout my childhood, I listened while my mom repeated the same story: how she’d reached out twice to the doctor who delivered me, hoping to learn something about my history. Both times, she was shut down. Warned not to ask again. This is something I’ve turned over in my mind more times than I can count—the idea that I was placed for adoption to have a "better life," and yet somehow, that didn’t include the bare minimum of dignity or care once I was born.

In the 1970s, closed adoption was standard practice. Centered on the mid-century ideals of privacy and protection, original birth certificates were sealed, ties to biological families were erased, and adopted children were left with no information about their history. Adoptive parents were told to raise us “as if born to,” while birth mothers — often young, unmarried, and shamed — were expected to forget and move on. For many of us, that silence became a lifelong search for truth, identity, and belonging.

A latecomer to motherhood, I gave birth to my first child at 35 - a daughter, via emergency cesarean. I remember feeling scared, actually afraid, that my baby would be injured by the lack of immediate skin-to-skin contact. I could not fathom how that time, those precious bonding moments, could ever be regained. Once out of recovery, I asked for my baby.

“Her blood pressure is elevated,” the nurse said.

“Bring her to me now,” I pleaded.

“Ashley, don’t upset yourself,” my mother said.

“I want to see my baby now!” I demanded, panic setting in.

Eventually, my husband wheeled our hours-old daughter into the room. I took my child —crying, scrunched up face, red as a beet — cradled her to me, and tried to breathe. After several minutes, the nurse commented that my daughter’s blood pressure was better. “Guess she just needed her momma,” she quipped. In a flash, for the first time in my life, I thought of my first mom as a peer, and I thought of myself as a distraught infant who just needed her momma.

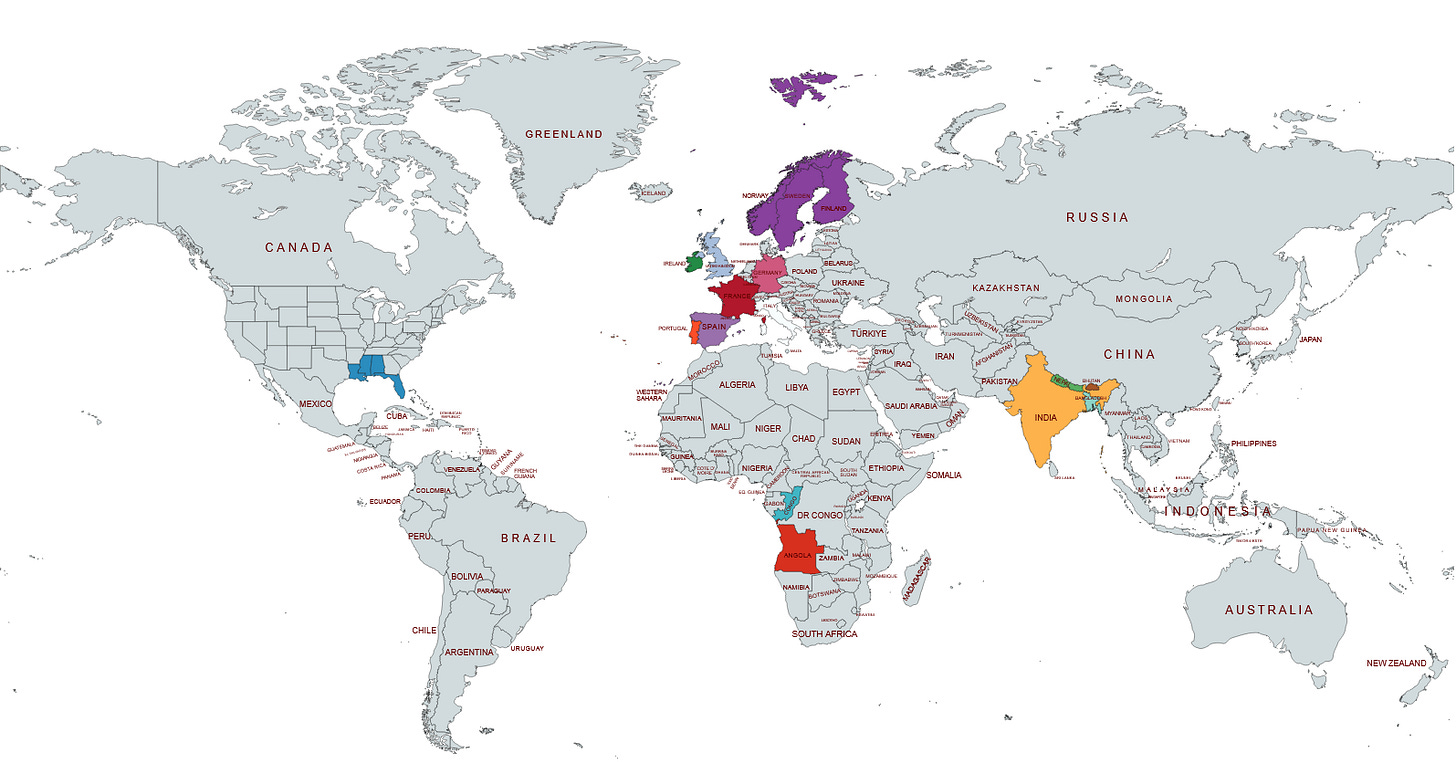

Reunion was never my goal, but I knew it was a possibility. As a lifelong fan of DC and Marvel comics, the idea of piecing together my own origin story was thrilling. After all, curiosity about one’s history is natural, seeking is healthy. Once I had my results, I felt a huge sense of relief having access to medical history for myself and my children. But for me, seeing the map of my lineage, brightly colored from one side of the world to the other, filled me with such satisfaction. I am all of those bright colors. I am mostly French and Irish, but I am also Portuguese, Native American, Congolese, and Bengali.

The experience of seeing that map, scrolling through the names of my DNA relatives, instantly grounded me in the knowledge that I come from somewhere, from a family. Not just a courtroom in Gulfport, Mississippi.

And while knowledge alone doesn’t create a sense of belonging, it offers a crucial first step toward transparency. By listening to adoptee voices and centering future research, policy, and practice on the lived experiences of adopted people, we can deepen our understanding of adoption trauma, build a framework that honors all voices within the adoption triad, and equip adopted individuals with meaningful, trustworthy tools to navigate the complex, often unseen layers of their experience. Only then can we move beyond silence and toward recognition, healing, and lasting change.

Adapted from Down the Rabbit Hole: The Mental Health Implications of Adoption Trauma on People Adopted at Birth

The Primal Wound

You get to the very heart of the problem of closed adoption when you talk about undergoing the extreme stress of being born to then lie in a cot not being handled or comforted by the person you, the baby, already know from being in utero. That is traumatic and acknowledged as such now.

It's a huge challenge for the adopters as well. There's always difficulty if your baby is colicky but if you're the adoptive mum it is even harder. If you're that baby all the trauma and stress may stay with you for life.