Who Even Am I?

Adolescence

Individuation, the process by which a person develops a clear, separate sense of self, is a normal developmental task of adolescence (Graafsma et al., 1994; Levine et al., 1986), but for adoptees, this process can be uniquely challenging. While adolescence is universally fraught with identity questions, hormonal shifts, and boundary-testing, adopted people face additional hurdles that often go unseen.

Research suggests that the absence of a solid identity foundation, one that includes historical, racial, and ethnic context, can leave adoptees feeling lost at sea (Graafsma et al., 1994). For some, these feelings are further exacerbated by secrecy around their adoption, limited access to medical or historical information, and/or a lack of open dialogue. Grotevant and Von Korff (2011) found that linking one's past, present, and future through open communication can help adolescent adoptees begin to construct a coherent identity. On the other hand, those denied openness may find the process of individuation stunted or deeply confusing (Grotevant & Von Korff, 2011; Lieberman & Morris, 2003; Passmore et al., 2006).

For transracial and transnational adoptees, these challenges are compounded. Many grow up in environments where no one looks like them, there is not shared cultural history, language, or belief system. To not know where you come from is one thing. To also not see yourself reflected anywhere around you is another entirely. Imagine growing up in a different culture, perhaps for years, while waiting for their adoption to be finalized and then BAM! Every aspect of your daily existence, every sound, smell, sight, relationship, and flavor changes on a dime. Now add to that a language barrier, unknown trauma history, and unknown or conflicting cultural and religious differences, and you’ve got some massive stressors that do not just disappear with time.

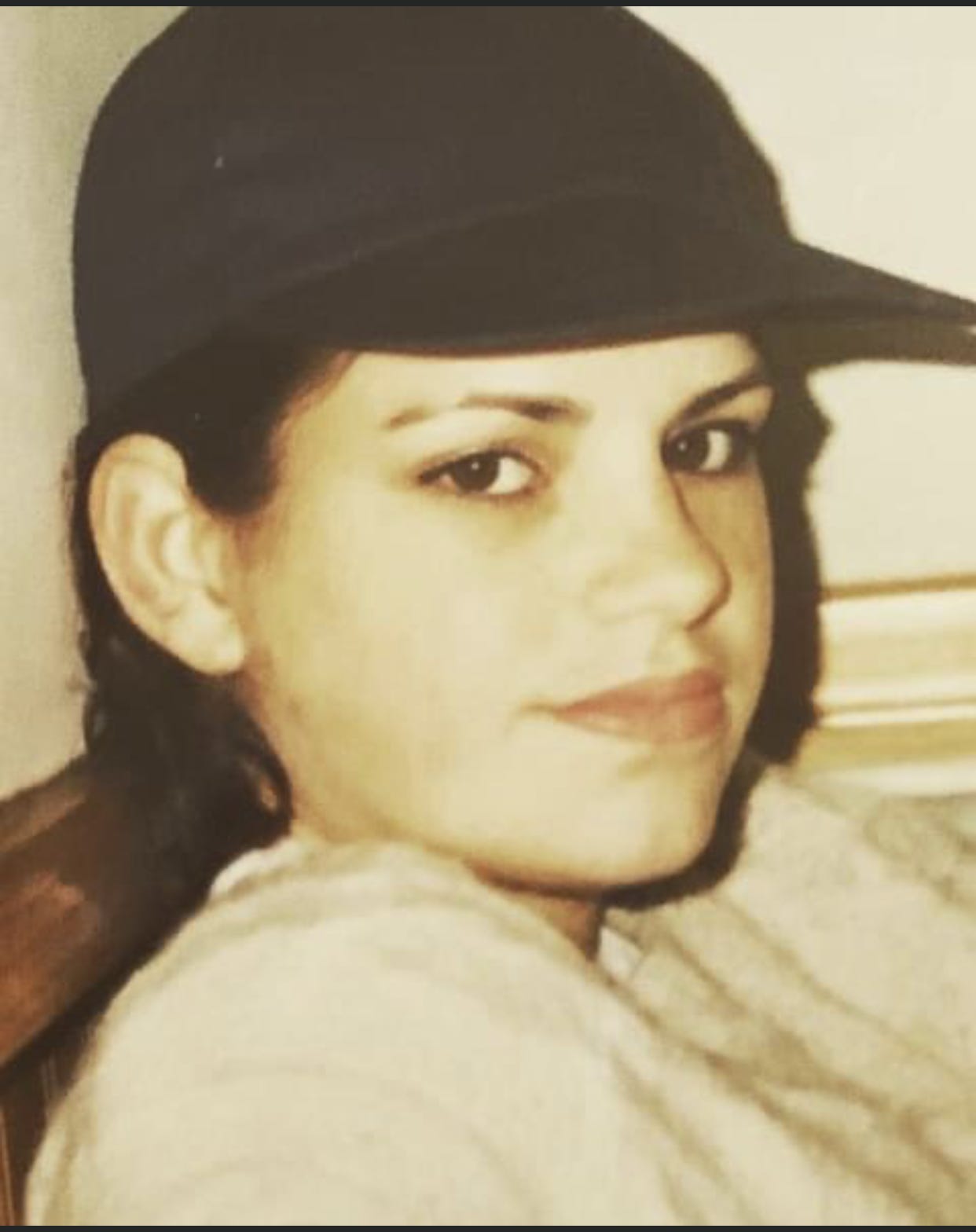

As for me? Adolescence and I were not friends. I really struggled during that time, spending years minimizing the self I knew in my bones while simultaneously trying to live up to expectations. Walking that razor’s edge is not tenable for anyone, and I was already a curious, strong-willed, some might say obstinate teen, so of course I started smoking. It was the '90s. I knew it was bad, but I was badder, and tobacco was just dangerous enough without being illegal. When my mom caught me, she had a total meltdown.

And to think I worked so hard to keep you alive! How could you do this to me?

It wasn’t the first time I became aware of what I felt were the unspoken conditions of our relationship: I saved you; you owe me. Live up to my ideal.

When I was nine, visiting my maternal grandparents in Mississippi, one of my Momo’s friends casually asked what I’d been up to. I answered with a movie I had just seen, a true story about a birth mother who regained custody of her son years after he was adopted. On the nine-hour drive home to Arkansas, my mother cried intermittently, spiraling.

What will they think?

Do you want to go to your birth parents?

Is that what you want?

How could you do this to me?

What’s wrong with you?

Why would you say something like that?

This became the pattern: Behaviors that challenged the carefully curated image = a personal attack on mom. I know now of course that many of her reactions, especially those around attachment, adoption, and perceived loyalty, were rooted in fear - fear of loss, fear of judgment, fear that the bond she worked so hard to build could be broken in an instant. After years of research and reflection, I’ve come to understand that many adoptive mothers internalize shame when others assume they couldn’t have children biologically. Other women report experiences of actual shaming from family members when they are unable to produce biologically related children. I know this happened to my mom, as she shared that with me in one of the few honest conversations we ever had about adoption from her perspective. That shame can manifest as insecurity, hypervigilance, and over-possessiveness. In my mother’s case, it led her to cling more tightly.

So, I would capitulate, little by little. I adapted, pretended, emulated. I learned how to “be” what others expected of me. I fought with my mother, with girls at school, with myself. Over time, any remnant of my authentic self blurred under the weight of expectation. Shocker! This led to big time struggles with intimacy, vulnerability, imposter syndrome, and a deep fear of rejection. I had no idea who I really was, only who I was supposed to be, and that my worth was inherently tied to maintaining the façade.

If you’ve ever read Ibsen’s A Doll’s House T, imagine Nora, I’ll invite you now to imagine the mother. This play struck way too close to home when I read it in college. My mom, poised and prepared, a thousand plates spinning at once, the picture of perfection, driven by the sole desire to fulfill her role as a wife and mother at the expense of her own mental health and well-being.

See? We’re a normal family! We’re just like you!

Then came the accident that changed everything.

It was 1992. I was 16, newly licensed, and thrilled at the chance to drive my mom’s car home after we picked her up from the hospital. When we arrived, it became clear her ankle was not sprained, it was shattered. She had surgery the next day, and not long after she developed a nerve disorder called reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD). What followed were decades of unrelenting nerve pain, multiple surgeries, and a dependency on narcotics that slowly altered the rhythm of our entire family life.

Let me be clear: my mother never would have become dependent on narcotics if she had not been injured. I believe this and so does everyone in our family. But the reality is, she lived with chronic pain for 32 years and she managed it with many prescription drugs. The toll on all of us was immense. She still showed up, staying involved at our schools and church, hosting dinner parties, birthday parties, planning vacations, doing all the cooking – I’m talking three meals a day, and even trying to work. When she was on she was on. But in the in-between, when she wasn’t performing, things were dark. Living with someone on long-term opioids is like playing a game of hopscotch on ice. At any moment, the surface can crack, and when it did, all bets were off.

After mom died, I found myself repeating old patterns - coldness, anger, distance, withdrawal, behaviors I had worked hard to address. So I found a therapist who helped me do the hard work of EMDR and the healing work of narrative therapy. Each session stitched me back together. Not into who I had been before, but into a stronger, more intentional me. I was awake. And for the first time in my life, I began to feel grounded in my body, in my truth. No mask. No role. Not the sum of someone else’s expectations. Just me.

Looking back, the day my mother died feels like kicking open a too-long locked door. Where estrangement from my birth mother left a vacuum, it also led me down a path to self-discovery. Likewise, in the midst of experiencing the most unbearable grief around my mother, something ancient cracked open in me, and suddenly there was space to begin the process of reclaiming myself.

In terms of human development, adolescence doesn’t end until around the age of 25, but for those of us who struggled with individuation and identity formation, lingering threads of adolescence can be a barrier to experiencing real freedom. Healing allowed me to cut that thread and move forward into new truths: I can love my mother and still resent her decision. I can hold anger and find forgiveness. I can view my adoption with sorrow and feel a sense of gratitude for the life I was given.

Moving into middle adulthood after losing my mom to suicide has been a massive shift. I am more vulnerable with myself and those closest to me than ever before. I allow myself to feel the pain now so I don’t end up living in it forever. I miss my mom. I miss the security of knowing I could call her at any time, day or night, and she would answer. I need her. I want to share stories about my children with her. I want to create new memories with her. I want to shake her and tell her that she didn’t have to die alone. I want to hold her like a child, heavy in my arms. I want to tell her I’m sorry and that I understand now.

I want to tell her I’m all growns up.

Your story of your struggles with identity and separating yourself and your adoptive mother's shame tells me again how much everyone in adoption stories is affected. I'm glad you've found therapy useful. Sadly here in Aotearoa New Zealand therapists are thin on the ground. 100,000 adoptees, birth mothers and adoptive families are subject to the rigours of closed adoption from 1950s to 1980s and mostly we are muddling through with help from people like you here online.

Thank you so much for sharing this beautiful, resonant piece. Your description of your teen years sounds like mine, and we are very close in age. I am so sorry you were met with the mom-centered reaction to your processing of experience, and that you lost her that way. Every adoptee story I read that resonates like this feels like a reassuring hand on my shoulder saying, "See? It wasn't just you". I understand the complexity of grieving a mom who caused pain, and that door-kicking open feeling when she passed. I'm gonna have to try EMDR, and read the Ibsen play. Thanks again.